My latest art-related mystery, Rituals of the Dead, is set in Papua and the Netherlands – two nations on opposite sides of the globe yet connected by a colonial past.

Dutch New Guinea

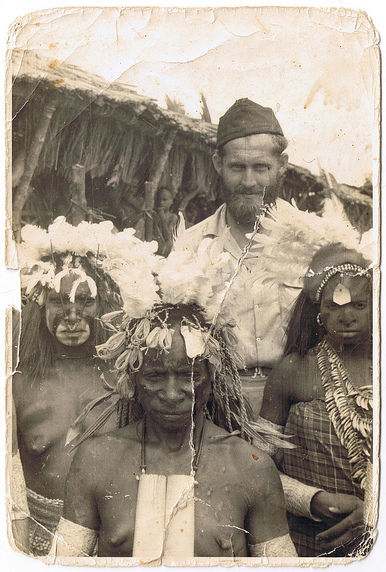

Dutch New Guinea – as the Papua Province of Indonesia was known until 1963 – was considered to be one of the last truly wild frontiers. The seemingly impenetrable interior and extreme weather, combined with rumors of headhunting and a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, enticed many explorers wishing to prove themselves as intrepid adventurers, and anthropologists hoping to document these ‘primitive folk’. It also attracted Western missionaries who wanted to drag the locals ‘out of the Stone Age’.

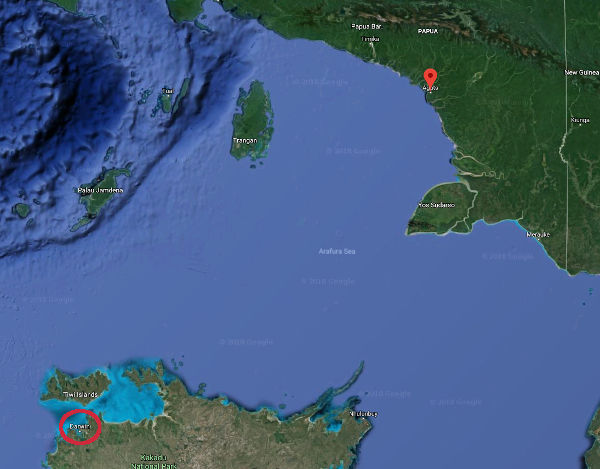

Hollandia (now Jayapura) was the capitol and main port of entry into the colony. Asmat is the name of a large province within Papua as well as an ethnic group that resides there. Agats was – and still is – the largest and most developed village in the Asmat Regency. It is the same town Western explorers would have flown or sailed into, and from there arranged transport further into the region. In Rituals of the Dead, my anthropologist Nick Mayfield follows a similar journey, flying from Hollandia to Agats where he pays locals to row him up the St. Lorentz River.

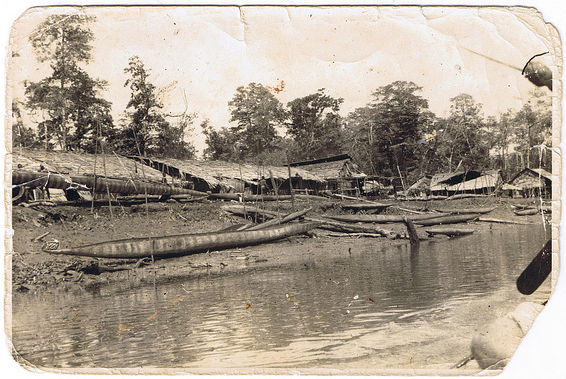

Boats were the only realistic means of transport back then because very few roads existed, and none connected the Northern part of the island with the Southern side. The St. Lorentz River – a short boat ride away from Agats – was the main transportation route for Dutch colonial officers, administrators and missionaries. As such, the villages along its banks are well-described in these explorers’ journals.

The Asmat: headhunters and world-renowned carvers

The landscape the Asmat inhabit is an extensive lowland swamp, dotted with tufts of rainforest, mangroves, and a maze of winding waterways. The tidal variations are extreme – three to five feet difference between ebb and flow is the norm – which is one of the reasons why their houses are built on stilts! I have also read that they are built high up like this to protect from predatory animals and – according to some – restless spirits that lurk close to the ground at night.

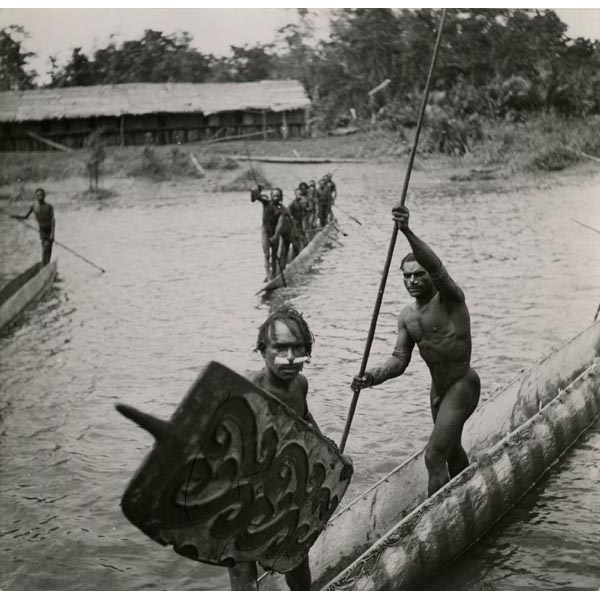

The Asmat carve exquisite bis poles, shields and paddles that were – and still are – greatly desired by Western museums and collectors. These ancestor objects were carved during a bis ceremony, a six-week long party honoring the recently dead which culminated in a headhunting raid.

In Rituals of the Dead, Dutch priest Kees Terpstra’s work as a missionary in the St. Lorentz River region is modelled after a real priest, Gerard Zegwaard. Zegwaard was the first Western missionary to really connect with the Asmat, win their trust, and eventually convert them to Catholicism. Though Western missionaries only gained a foothold in the region in the early 1950s, their impact on the Asmat’s spiritual lives and artistic expression were profound. By the time the Dutch ceded their control of the region to the United Nations in late 1962, in many areas headhunting rituals had already been replaced with Christian church services. The carvings’ scarcity only helped to drive up the prices and attract more and more anthropologists to the region, interested in buying everything they could find. These collectors inspired my character Albert Schenk, an anthropologist who documents the Asmat as well as barters for artifacts on Dutch museums’ behalf.

Roughly half of my latest novel is set in the Asmat region in 1962, months before the Dutch let their colony go. In these chapters, my characters live in a village called Kopi. It is located on the St. Lorentz River about five hours from Agats. This fictitious village is based on a conglomeration of actual villages and settlements built along the river’s banks, as described by westerners working in the region in the 1940s through 1962. I relied heavily on their written accounts when describing the layout of Kopi, division of tasks, and typical daily life.

Though I have never been to Papua, I did live in Darwin, Australia for almost two years while studying cultural anthropology and aboriginal art at the (now defunct) Northern Territory University. My former home was directly across the Arafura Bay from Papua, the location I would set this novel in – twenty years later! (Trust me, if I’d known I’d one day write about Papua, I would have made a point of visiting. Though at the time, extremely violent clashes between the Indonesian government and indigenous groups in East Timor and West New Guinea may have made that impossible.) I also spent a month exploring Fiji, another island in the Melanesian group that shares a similar flora, fauna, and climate to Papua.

These experiences allowed me to better imagine the smells, sights and sounds my characters would have experienced, so well documented by early and contemporary explorers in their written accounts and documentaries.

Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam

This is my second novel set in the Netherlands – and in particular Amsterdam. In both, my main protagonist Zelda Richardson is studying art history while interning at different Dutch museums. The beauty about living in one of the settings is I can hop on my bike and research potential locations! The Lover’s Portrait revolves around artwork looted during World War Two, making the Amsterdam (Historical) Museum, Jewish Historical Museum, and City Archives natural choices as settings. Because Rituals of the Dead involves anthropological artifacts, I chose two fascinating museums as the main Dutch settings – Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum (Museum of the Tropics) and Steyl’s Mission Museum.

In my latest novel, Zelda Richardson is interning at the Tropenmuseum and one of her projects is conducting collection research for an exhibition of Asmat art. This was not a random choice. In 2008, I worked as a collection researcher for an exhibition of Asmat artifacts – Bis Poles: Sculptures from the Rain Forest. It showcased all of the bis poles owned by Dutch museums and described their collection history and spiritual significance. It was held in the Tropenmuseum, which is famous for their impressive Papua and New Guinea collection. They also have a fascinating exhibition about the Netherlands’ colonial history and life in Dutch New Guinea. This museum’s history, as well as the wild stories I discovered while researching the Asmat collection, directly inspired Rituals of the Dead.

You can read more about the Tropenmuseum and their bispoles in this post. You can also read more about the colonial origins of Western ethnographic museums in this post.

Mission Museum in Steyl

I first visited Steyl’s Mission Museum in 2006, as part of a museum studies class. This relatively small – yet extraordinary – museum displays artifacts and relics collected by missionaries stationed around the globe. Their exhibitions left a deep impression on me. When I decided to write a mystery about ethnographic artifacts, the Mission Museum sprung immediately to mind as a potential setting.

Steyl is a small monastery village in the southernmost tip of the Netherlands. It was founded in 1875 by Father Arnold Janssen as the home for his newly established Steyl Mission Congregation (S.M.C.). The Mission Museum was created in 1889 to provide parishioners a glimpse into mission life and the countries (often colonies) their missionaries were actively working in. The classification system hasn’t been updated since 1931, though pieces are still added to the collection.

One small room is filled with an incredibly selection of butterflies, praying mantis, grasshoppers, beetles, and other insects. A second, much larger room is divided into two sections. On the right-hand side are stuffed animals – birds, primates, and large mammals – displayed as if they were still alive. The ethnography collection fills the left-hand side. The objects are divided by region: Japan, Netherlands Indies (now Indonesia), Papua New Guinea, and Africa. The displays are a fascinating jumble of utensils, weapons, shields, handcrafts, carved sculptures, human remains, body decorations, and ancestor objects. A shield and the human skulls displayed here even have a starring role in my novel!

You can read more about the Mission Museum in Steyl in this post.

I hope this gives you a better sense of the settings used in Rituals of the Dead. You can pick up my artifact mystery on Amazon COM, Audible US, Barnes & Noble, iBooks, or your favorite online bookstore. Click here for more direct links. Happy reading!

** In the image featured above the headline, you see Papuans, a carved Asmat shield and a Men’s House in the background. [Copyright Man Cultural.]

Thank you – so glad you enjoyed it!

Fascinating!