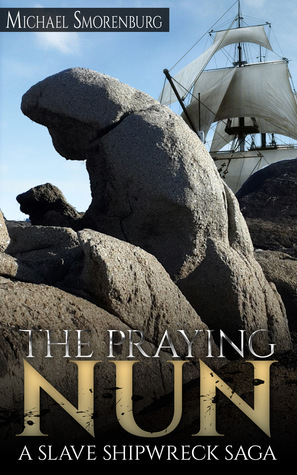

Today I’m thrilled to share my review of the excellent novella, The Praying Nun with you and a guest blog post by author Michael Smorenburg entitled ‘Cracking open Davey Jones’ Locker’.

The Praying Nun

The Praying Nun is a thrilling adventure novella about two South African men’s attempts to salvage objects off of a shipwreck off the coast of Africa.

The Praying Nun is a thrilling adventure novella about two South African men’s attempts to salvage objects off of a shipwreck off the coast of Africa.

Situated at the Southern tip of Africa, Cape Town is built on a dangerous stretch of coast known as the ‘graveyard of ships’. In nearby Clifton Bay, two local men – the author and his friend Jacques – suspect they’ve found artifacts from a sunken Dutch VOC ship rumored to contain gold bullion. Well, Jacques does anyway. The government office which issued their salvage permit thinks it is a coal barge that went down in the late 1800s. The author, Michael Smorenburg, believes the objects they’ve found to be from a slave ship that went down in 1794.

This novella is split into two distinct parts. The first, the mostly autobiographical portion, recounts their efforts to recover any objects or relics from the ship – a cannon, wooden beans, and lots of conglomerate – so they can correctly identify the ship before attempting to excavate it. Conglomerate is a hardened accumulation of dirt, mud and rock that fills in and eventually encases any object left on the ocean floor. This makes it extremely difficult for divers to know exactly what they’ve found until they take the time to carefully chip the outer layer away and hope that the object doesn’t break in the process.

Jacques is only interested in the wreck if it’s the VOC ship because the gold would make the operation worth the risk and costs. But a coal freighter or slave ship wouldn’t bring any money in. Michael agrees up to a point, but is also fascinated with the possible historical value it would have, if it is indeed the slave ship. Both agree a coal freighter is not worth the risk.

Because so many ships went down in the area, it could easily be any of the three. Much hope is pinned on the recovery of a cannon that – after an extreme amount of work to remove from the wreck and get onto land – turns out to be a bust, making Jacques lean towards the coal freighter theory and begin to lose interest.

The wreck site is dangerous to reach and both men have to break off several dives attempts due to changing currents and incoming storms. This is a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants operation – the men have little money to spend and rely on the goodwill of friends and acquaintances to scrap together enough equipment to dive safely.

The dives are brilliantly described. You feel as if you are in the water, fighting off exhaustion, low oxygen levels, murky visibility and biting cold, each time you go down. Their frustrations and the challenges, as well as their determination to go on, ring true thanks to the author’s ability to bring his readers ‘into the moment’.

At the end of part one, the Smithsonian Museum has correctly identified the shipwreck as the slave ship Sao Jose Paquete Africa.

Though it may seem as if this review is full of spoilers, I don’t see it that way. The novella’s strength lies in the author’s ability to make these dives and the suspense of discovery, tangible.

The second part of the novel is a fictitious historical account of the slave ship’s last days, based on the extensive records, news reports and journals found by the author in local archives, accounts written by the Captain, crew and locals who witnessed the disaster or its aftermath.

Though somewhat disturbing to read, it does add value to the book by providing a glimpse into the horrific conditions aboard.

The Praying Nun is an excellent, real-life adventure story that adventurers, amateur archaeologists, divers, treasure hunters and adventure fiction fans will love and probably relate to. I highly recommend it.

5 out of 5 stars

Cracking open Davey Jones’ Locker

By Michael Smorenburg

There is an irresistible romance associated with sailing the oceans, with the brave adventurers who chanced their lives on wild oceans.

Adventure is, after all, at the heart of humanity’s success as a species… we are all the children of ancestors who left the cave, beat the predators and odds, and handed their adventurous genes on to us.

This intrinsic urge to travel was spurred by storytelling. Tales have always jangled our sense of awe and wonder for discovery. This seems true for every culture – it is what inspired new generations to move over the next mountain and eventually out over the horizon.

But where we sail, we eventually wreck.

Ocean storms are indifferent to our ambitions, and the craft our ancestors designed for the docile waters of the Mediterranean and European coast were tragically ill-prepared for the open oceans.

Of course, the notions of anything vaguely pleasant or exciting about ancient shipping and the wrecks that they left is entirely illusionary. The transits were brutal, discipline barbaric, crews cutthroat… being criminals or drunks pressed aboard.

Every enterprise has a budget, and until into the 18th Century, the list of expendables extended to ‘acceptable’ loss of life. The quaint notion we hold today of all crew members returning home as a management goal was unheard of.

Captains put to sea with the full expectation sanctioned by their masters that up to 30% of a company might perish en route of malnutrition, ordinary sickness and regular accident.

And then the ships… those dreadfully ill-prepared early ships.

They were, by all modern standards, horrific in design and operation.

Driven by wind, they mostly rode ahead of the weather, whatever direction it might blow.

Modern sailing ships have designs that allow them to sail across the path of the wind and even into it – but the craft of old could barely ‘go to wind’ at all.

And there was no pre-warning of onrushing storms.

Mariners knew they were in for a tempest only when the dark dread of it appeared over the horizon.

There was nobody to call to for help, no way to call, and no more able rescue craft to come to aid and brave nature’s onslaught than the ship’s own ability to ride it out.

As if nature had a malevolent bent, all too often (and due to physics and metrology) it seems that prevailing storms conspire to blow toward land, breaching ships onto deadly reefs within sight of land, but divorced from land’s safety by mountains of waves, boiling water and treacherous currents.

It is no wonder that the seas of the world were thought to be governed by their own set of gods, Neptune at their helm.

Seafarers dashed onto rocks within hailing distance of land’s safety were as unlikely to survive the violence of shallow water as they would be if pitched into open ocean out of sight of land.

And so it is that, with this much danger and probability for survival, we must consider why anyone would invest into excursions and put to sea at all.

The obvious answer is trade and cargo.

The first of the European explorers were not after glory, they needed spices to fill the demand to improve the bland diets of burgeoning European populations.

Of course, spices lost in a wreck are of no value at all to a modern treasure hunter – but the salvage of a bronze cannon old salts used to protect their haul have real worth.

That said, I know of a case—a friend—who salvaged a Portuguese ship from the late 1500’s and found pepper corns locked into the wreckage. These needed to be dredged out before more valuable treasures might be revealed below that layer.

As it happened, the pepper corns were sieved and retained, and when dried they proved to be of an excellent and enduring quality that found a market half a millennium after their intended target customer was gone to the grave.

There is of course always the prospect of gold and other treasure. Without the benefit of Letters of Credit and Internet Transfer, traders of the day had to carry chests full of shiny things to barter and pay with.

If you are lucky enough to find a ship wrecked on that juicy gold-rich leg of their journey, you may well retire in splendor.

But the ocean is a very big haystack and troves of valuables are a lot smaller than proverbial needles in that ratio of seeking and finding.

The wrong thing to do is to start looking for wrecks.

The right place to start is in archives, where the ancient records lie waiting for new eyes and keen brains to pick apart the riddles of confusion that often dog ancient record keeping.

Without GPS and only laborious methods of navigation, the last thing on a seaman’s mind during a fight for life, is to accurately mark the site of a ship’s demise. Fear skews perception, so that the proverbial “X” eventually assigned on a chart to a vessel’s final resting place might well be leagues and more misplaced.

Hunting a specific ship and its cargo becomes detective work, and as with all modern inventions, into the fray now comes new technologies unimagined by rival and failed explorers of a generation and more ago.

First came side-scan sonar. Sonar is the radar of the aquatic world. It allows a crew to remain warm and dry inside of a cabin while peering at the bottom features of an ocean using sound and its reflection.

Computerization has allowed modeling that can pick up on nuances that in past models of the technology would have gone unnoticed by human eyes. These scans can now be imaged to fabulous resolutions of detail and differentiate materials held by the ocean’s floor, its reefs and sand. Wood, steel and other non-natural arrangements at the bottom of an ocean can stand out like a beacon with sensitive modern equipment.

And now we enter the era of the drone, when a landlubber can remain ashore and let the flying robot skim autonomously over the sea on a laborious GPS guided grid pattern, missing nothing and complaining not at all.

Latest advances will very shortly unwrap surprising mysteries – and of course… loot!

I am in contact with a group in Australia who are very close to overturning the official history of that region and its founding. What looks like a Spanish galleon from the late 1500s lies entombed there in a bay, consigning Captain Cook’s claim to history and assigning a new founder in his place to seize his crown.

Watch this space.

Author’s Bio

Michael Smorenburg (b. 1964) grew up in Cape Town, South Africa. An entrepreneur with a passion for marketing, in 1995 Michael moved to California where he founded a business consultancy and online media and marketing engine. In 2003 he returned to South Africa where he launched then sold a security company. He now operates a property management company and writes full time.

Michael Smorenburg (b. 1964) grew up in Cape Town, South Africa. An entrepreneur with a passion for marketing, in 1995 Michael moved to California where he founded a business consultancy and online media and marketing engine. In 2003 he returned to South Africa where he launched then sold a security company. He now operates a property management company and writes full time.

Michael’s greatest love is for the ocean and the environment. His passion is science, understanding the cosmos, and communicating the urgent need for reason to prevail over superstition.

His dedicated author’s website and pictures at: www.MichaelSmorenburg.com

The Praying Nun – A Slave Shipwreck Saga

Based on Facts – “The Praying Nun” is a 2-part novella that details the first attempts to identify an unidentified shipwreck from cannonball, cannons & artifacts found just behind the waves of one of the world’s most beautiful beaches.

In 2015 the Smithsonian Institute identified that wreck as the only slave shipwreck ever found. She went down in 1794 – half of the 400 slaves chained in her holds were drowned – and the other half who were ‘saved’ were sold 2 days later on the block.

Watch this incredible video about the story of the São José Shipwreck here.

Pingback: Spotlight On… – Jennifer S. Alderson